Indigenous and RecoSal participation in ICES Annual Science Conference: Merging Indigenous knowledge with fisheries science

Indigenous scholars and organizations had a strong representation at the ICES Annual Science Conference in Klaipeda, Lithuania on 15–18th of September 2025. ICES stands for the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, an intergovernmental scientific organization that both develops science and gives advice to member states in all matters concerning the North Atlantic.

For the first time a theme session on the topic of indigenous knowledge was organized at the annual conference. ‘Approaches to the inclusion of Indigenous and local knowledge in fisheries management and policy development’ offered multiple perspectives on inclusion of local and Indigenous knowledge in marine science, both at the theoretical level and with substantial examples (see program in the end of the text). The session was co-convened by Stine Rybråten (NINA), Karen Dunmall (DFO), and Daniel Goethe and Kristen Omori (NOAA).

The session discussions were primarily oriented towards indigenous knowledge topics, which highlighted the importance of bridging communication gaps and repairing trust within communities that have suffered from knowledge extraction, institutional instability, and lack of recognition of sovereign rights. Therefore, manifesting change in fisheries management systems to better accommodate co-governance will require acknowledging Indigenous rights, early integration of Indigenous leaders, adapting systems to accommodate alternative approaches to science and communication, and acceptance of novel community-based management solutions.

The RecoSal and Sharing Our Knowledge projects were strongly represented during the first sub-session ‘Indigenous and Local Knowledge in the Arctic’ that explored indigenous inclusion in European and North American Arctic regions. Associate Professor Camilla Brattland (UiT, RecoSal and Sharing Our Knowledge projects), Research Professor Jaakko Erkinaro (LUKE, RecoSal project leader), and Research Professor Juha Hiedanpää (LUKE, RecoSal project), as well as dr. Shelley Denny (UINR, Sharing Our Knowledge project) all presented at the session.

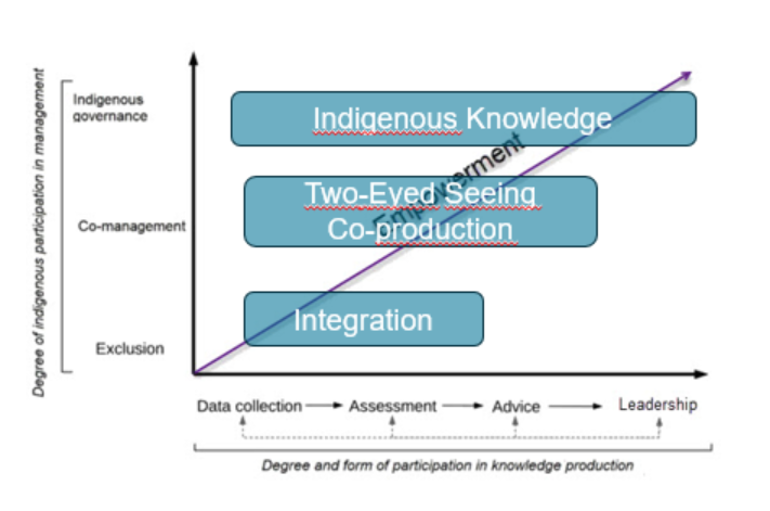

Brattland’s keynote presentation, that opened the session, was titled ‘Inclusion of Sámi and local knowledge in northern fisheries management and policy development’, based on an upcoming paper in a special issue on inclusion of Sámi in salmon governance in Arctic Anthropology. The main case in point was the diversity of ways and dimensions along which Indigenous knowledge could be merged with science (See figure 1). This question was addressed not only in the session where RecoSal participated, but also in other sessions and by poster presenters at the conference. As a response to the community poll posted by Brattland, one of the participants quite rightly pointed out that there may not be one best way of merging Indigenous knowledge with science, but that it is more a question of adapting the right approach to the task at hand.

Brattland in particular discussed the case of development of Sámi agency in Norwegian whitefish fisheries management, relative to the level of Sámi participation in salmon knowledge production and governance in the cases of the Deatnu - Tana and Njâuddam - Neiden rivers.

As a tool for analyzing the level of empowerment of Indigenous actors in fisheries governance, she presented a model which places participation along the dimensions of governance and different forms of knowledge production (see figure 3). In essence, the level of empowerment in fisheries governance depends on the degree of self-governance and the extent to which the knowledge basis for management recognizes Indigenous knowledge as a valid basis. How can Indigenous groups then climb up the ladder of empowerment? First of all, there needs to be recognition of Indigenous rights to natural resources and to participate in management. Even though the right to participation is recognized to some extent in the Norwegian fisheries management system, there is little recognition of historical fishing rights, which places the Sámi less than halfway up the ladder. One way to move further up is to secure the recognition of historical rights and establish a management body with Sámi self-determination or strong participation. Measures to strengthen self-determination such as quotas to prioritize fisheries as a material basis for cultural survival and higher participation in management are additional means. Unresolved questions are whether arrangements such as co-management, with equal Sámi representation in a state governance body, can ensure the cultural foundation, and also how principles such as respect, equality, and wisdom can be maintained in the statutes and principles of governance without recognition of Indigenous historical fishing rights.

In other Indigenous contexts, it is not only about establishing governing bodies with an Indigenous majority but also about ensuring Indigenous values and principles. Brattland touched upon examples from the Mi'kmaq context, which are comparable to emerging principles which could be relevant as guiding principles also for Sámi participation in Norwegian state fisheries governance. One principle is maintaining the balance of nature (Netukumlik), comparable to the Sámi concept of birgejupmi (harvest for self-subsistence), and "Two-Eyed Seeing," comparable to recognizing Sámi traditional knowledge on an equal footing with science. In other Indigenous contexts this is reflected in institutional governance, for example, by ensuring that Indigenous councils (tribal councils) both set the premises for governance and oversee that it is carried out in accordance with the Indigenous values that the management is supposed to uphold.

In the next presentation, Jaakko Erkinaro talked about the rapidly evolved situation, “the Great Reset”, at the Deatnu river with a collapse of the native Atlantic salmon population and the surge of the invasive, alien pink salmon. This dramatic change in the Deatnu valley’s way of life, Sami fishing culture and tourist business, including the Atlantic salmon fishing ban, is calling for ways of using traditional knowledge in planning new fishing opportunities. Examples include designing novel methods for targeted pink salmon fishing based on traditional Sami fishing techniques, and establishing fishing areas for sea trout angling, which mainly aims at building opportunities for local businesses in maintaining some recreational fisheries for tourist anglers. Both approaches involve a strict aim of avoiding Atlantic salmon bycatch in a situation with strongly declined stock status.

By building on Erkinaro’s presentation, Hiedanpää introduced an action-oriented methodology that is participatory and iterative, focusing on solving, overcoming, or coping with real-world problems, such as the impacts of the pink salmon invasion in the Teno River. In action research, Indigenous and local communities join with scientists and decision-makers to solve problems, forming what can be called a community of inquiry, and this becomes the first critical step towards epistemic governance.

Presenters in the rest of session one discussed examples and case studies of using indigenous knowledge to develop food security adaptation strategies and inform scientific models of species distributions. Key conclusions from this session were that Indigenous communities and cultural needs were often given secondary status to commercial harvest priorities and were often lost in the complexities of trans-boundary (state, federal, international, and sovereign territories) management jurisdictions. Moreover, Indigenous scholars often observed a disconnect between scientists working at the community level and management decision-making that rarely engaged locally. Concerns were raised that the lack of meaningful management action resulting from scientific interactions could lead to burn-out within communities due to limited progress gained from engagement. Increased funding for Indigenous scholars, who are uniquely equipped to handle communication across divergent groups and scientific disciplines, might help maximize community engagement and reduce burnout of community leaders.

The second session ‘Indigenous and Local Knowledge in the Atlantic’ was opened by Shelley Denny from the Eskasoni Mi’kmaw First Nation in Canada. Her keynote presentation titled ‘Doing ‘Treaty’ in the 21st Century ‘ focused on the concept of Two-Eyed seeing and the applicability of interactive governance approaches to inclusion of Mi’kmaw in the eastern Canadian fisheries management system. One key point was the importance of shared values as a possible bridge between different knowledge systems. Subsequent presentations then explored some specific interactive solutions such as how local knowledge could be better collected and utilized through online platforms, interviews with local communities and stakeholders, and the use of historical and community recognized place names to improve communication.

During the following discussion, the Norwegian Sámi Parliament, who was present at the conference, asked what the ICES could do to include indigenous knowledge and Indigenous peoples into its own systems (see figure 5). An ICES representative who was following the session answered that Indigenous peoples were welcome to attend working groups, which all are open to participation also by non-scientist experts. ICES is moving forward in including Indigenous peoples as rights holders and knowledge holders through the work of the Working Groups, such as a new working group on engagement of stakeholders (WGENGAGE). At the same time, they recognized the slow pace of change internally in ICES – exemplified by the fact that discussions on including social sciences in ICES started in the 1960s, while the new working group started their work only in 2024.

While it is great to say that everyone can participate, there likely are still barriers to participation based on background, experience, and funding constraints. Moreover, the model-based, quantitative approach to ICES advice may not be conducive to alternative ways of talking and thinking about human-biological systems. Two-Eyed seeing was discussed as a necessary tool for inclusion of indigenous knowledge and people in ICES processes. The Sámi Parliament also pointed out that the advice that ICES gives to member states should include the implications the advice has on indigenous rights and livelihoods. Jan Erik Henriksen (Arctic University of Norway), work package lead for the EU project Birgejupmi also brought to the discussion the responsibilities of ICES to implement indigenous ethical research protocols. Indigenous communities must be included in research projects as partners from the get-go to decolonize fisheries research.